kyle wind / Published: October 29, 2017

kyle wind / Published: October 29, 2017

After Rosemarie and Leo Yaeger built a new house in 2016, the couple was puzzled to learn their property tax bill was higher than some of their Scranton neighbors whose houses dwarf their 2,400-square-foot single-story home.

The pair appealed their East Mountain property’s assessment twice, eventually getting the figure reduced to $44,500 — which is still more than some opulent homes in the nearby Mountain Lake Estates.

“It’s nothing against (my neighbors),” Rosemarie Yaeger said. “I’m very willing to pay my fair share. I have no problem with it, but I shouldn’t be paying more than houses that are twice as big as mine.”

Voters will decide Nov. 7 whether Lackawanna County commissioners should borrow up to $13 million to conduct the county’s first property reassessment in nearly a half-century to more fairly distribute school, municipal and county real estate taxes. However, a panel of judges heard arguments Friday to remove the question from the ballot or to invalidate the results because the wording is “vague, misleading, ambiguous, distracting and confusing” and thus unconstitutional. The judges have not yet issued a ruling.

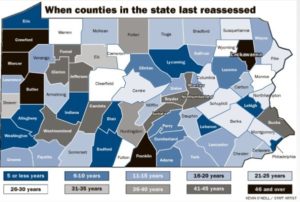

Lackawanna County’s property assessments are the second-oldest in the state, ahead of only Franklin County in southcentral Pennsylvania, which last reassessed in 1961 and has about 70,000-plus parcels, according to surveys from the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Farmland Preservation.

The Yaeger family’s experience could be the tip of the iceberg, reassessment proponents say, in a county riddled with unfair and inaccurate assessments that determine tax bills.

Opponents of reassessment say some elderly residents who live on fixed incomes are particularly vulnerable. Recalculating the value of their homes for the first time since 1968 could cause their property taxes to surge, they say.

Connie Williams, 74, who bought her grandmother’s Glenburn Twp. home in 1973, fears she could lose the house if a reassessment drives up her real estate taxes.

Williams estimates she lives on $18,000 a year from Social Security and a small pension from her late husband’s job at Roadway Express, with about 10 percent of her income earmarked for property taxes.

“I’m at a place now where I don’t have any money left, and if they up my taxes, I’ll be in the street,” she said. “I’ve lived here all my life. I love it here, but I just can’t afford any more taxes.”

Williams and the Yaeger family represent the divide between opponents and proponents of reassessment.

“People are tapped out,” said Lackawanna County Commissioner Laureen Cummings, who opposes reassessment. “People say I’m fear-mongering when I talk about how many (homes were sold in upset sales). I’m not fear-mongering. I’m truly concerned about those people.”

Proponents stress that reassessment is necessary to remedy the inequities facing property owners paying more than their fair share of taxes annually while others pay less. With reassessment, assessments for individual properties will rise across the board, and millages would be lowered to compensate. Reassessments do not raise additional money; they are intended to redistribute the tax burden. Roughly one-third of property owners will pay higher taxes, one-third will pay significantly lower taxes, and one-third will pay about the same.

The high number of assessment appeals demonstrate the costly price of outdated assessments, proponents say.

Between 2014 and last year, 1,290 successful assessment appeals reduced the county tax base by $44.4 million, The Sunday Times found. That does not include scores of appeals of new assessments after improvements or new construction. Many school districts are taking legal action to appeal the assessments of commercial properties that school officials say are grossly undervalued, the newspaper also found.

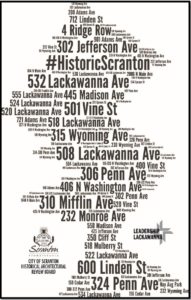

Not reassessing also adds to blight in neighborhoods and downtowns, said commercial real estate agent John Cognetti, who favors reassessment.

Homeowners who bear disproportionately high tax burdens often lack leftover money to properly maintain their homes, he said, and highly assessed commercial properties whose original owners move on become too expensive to maintain.

“The biggest taxpayers are people who have moved into this region and built brand-new industrial facilities,” Cognetti said. “As those buildings were vacated, the tax burden on a vacant building is so high, the building deteriorates. Whoever buys it next comes in for an appeal because the (assessment) is no longer relevant. It’s worth less money, so it sells for less money. It goes on and on and on and on.”

Cognetti said some clients have walked away from buying property rather than deal with the outdated assessment system.

“When people come in and ask us about taxes and how they’re assessed if they’re going to build a new building, we have to do a little bit of a dance to explain it to them,” he said. “You say, ‘Well, you have to go do a tax appeal.’ They look at you and say, ‘Why do I have to do a tax appeal? It should be like every other modern community that (reassesses) on a frequent basis.’”

Contact the writer:

kwind@timesshamrock.com;

570-348-9100, x5181;

@kwindTT on Twitter