For most people in Northeast Pennsylvania, Interstate 81 is a convenient way to get around.

Increasingly, the highway has become the region’s defining feature for real estate professionals, who have dubbed Northeast Pennsylvania by the terse, inelegant moniker “I-81 Corridor.”

I-81 Corridor has popped up in the past. But about four or five years ago, local economic development officials first started hearing it in conversations with corporate real estate professionals they were helping to find a suitable home for a business.

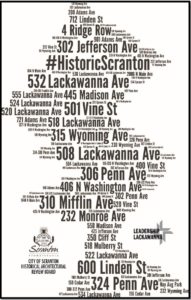

Soon Scranton, Wilkes-Barre and Hazleton began to be referred to as the I-81 Corridor in market reports by big commercial real estate firms like Cushman & Wakefield. After many years and many attempts to develop and promote a regional brand both for tourism and economic development – one finally caught on, but not any of the ones promoted from within.

As a brand, “Northeast Pennsylvania” was bland and vague. In the 1980s the Economic Development Council of Northeastern Pennsylvania came up with the handle “Pocono Northeast.” In the late 1990s, an outside consulting firm floated the term “The Great Valley” to unite the region from Hazleton to Carbondale. “Penn’s Northeast” was a personal way to refer to this part of the state, prompted by the economic development marketing firm of the same name. After several parallel efforts, some questions remain. Do the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre and the Poconos areas even belong lumped in with each other? What about the Endless Mountains region, the once-overlooked, now hotbed of economic activity with natural gas drilling and pipeline and power plant construction?

Relationship status

As someone may say of a dramatic relationship: It’s complicated.

There are challenges to branding the region. Unlike major metropolitan areas, Northeast Pennsylvania, however delineated, doesn’t have a single dominant city. Rather it’s a collection of cities, boroughs and townships, noted Phil Condron, head of a local creative agency and former interim chief of the Greater Scranton Chamber of Commerce. So ideas modeled after Chicagoland and Hotlanta are not an option, Mr. Condron said.

After you get past Lackawanna and Luzerne counties, there is the question of what else to include. The broader region has conflicting identities. The Poconos as a resort area; the Endless Mountains as rural area, now as center for the natural gas activity; and Scranton/Wilkes-Barre as a post-industrial population center.

The metropolitan statistical area is not reliable because it has been so fluid, subject to change after every census. Scranton and Wilkes-Barre were separate metro areas until the 1970s, then Monroe was added. The metro was redrawn to include Columbia and Wyoming counties. Then Monroe was dropped in the 1990s, followed by Columbia.

As economic development officials throughout the region began considering working together, the relationship with the Poconos has been on again, off again.

‘A Place to Grow’

In the late 1970s, when the sparsely populated resort area began to see the early incursion of permanent residents, the Economic Development Council of Northeastern Pennsylvania took notice and concluded the population would continue to increase and move west toward Lackawanna and Luzerne counties. The group came up with a branding campaign: “Northeast Pennsylvania – A Place to Grow.” Howard Grossman, who led the organization at the time, said the goal was to have, in as few words as possible, a brand that communicated a region emerging from the legacy of coal, and growing a new economy while providing an environment to raise a family and foster a business. The Poconos had name recognition and Northeast Pennsylvania had the infrastructure and labor. The agency encouraged local economic development groups to use the logo and many did. After six years, the funding ran out, Mr. Grossman said, but he’s happy to see the term has continued to be used by some groups.

The Poconos had a high-profile reputation, but as the Honeymoon Capital. The heart-shaped tubs didn’t mesh with the industrial ambitions of Scranton, Wilkes-Barre and Hazleton, Mr. Condron said.

“The Scranton and Wilkes-Barre areas wanted to brand themselves as a workplace, and Monroe’s image as a vacation destination didn’t seem to fit,” Mr. Condron said. “Sometimes, we have a reluctance to connect.”

Regional tourism efforts are a bit more creative. Still, a study in the 1960s floated the term “Playground of the Megalopolis.” Ideas improved and years later, a regional tourism alliance promoted the sylvan-sounding “The Great Northeast Territory,” and more recently an 11-county grouping known as “Upstate PA,” playing on the notoriety of Upstate New York. Tourism lends itself to a broader region since the number of attractions provides an additional draw.

Since the days of Pocono Northeast, that region developed its own industrial infrastructure. In the new era of regional cooperation, Monroe County, and often its neighbors, are at the table, participating in efforts such as Penn’s Northeast, Wall Street West and the new Biosciences Initiative.

Call us what?

For Northeast Pennsylvania, coming up with a branding turned out to be like giving yourself a nickname. It doesn’t stick unless someone else gives it to you.

Still, I-81 Corridor works for most to the extent it catches attention of corporate real estate professionals.

Someone of limited geographical knowledge may scratch their heads if they hear Penn’s Northeast, Pocono Northeast or Great Northeast. But I-81 Corridor resonates with anyone who has driven or reviewed a map of the mid-Atlantic states, said James Cummings of Mericle Commercial Real Estate and former executive director of Penn’s Northeast. He’s seen people outside the region struggle to define it. Outside commercial real estate professionals call South Central Pennsylvania “South Central Pennsylvania.” They call the greater Allentown area “The Lehigh Valley.”

“They didn’t call us Northeast Pennsylvania, or weren’t sure where it began or what it included,” he said. “Now, not only do they know I-81 Corridor, but they know their clients will expect them to pay attention to it – and us. We are now in the game more than before.”

Mr. Condron remembers when a drive down I-81 would feature the culm fire at the former Marvine colliery and one of the nation’s largest auto salvage yards. Now, one sees a ski resort, a modern office park, a sports stadium and shopping districts. Scranton has newfound recognition with the NBC sitcom “The Office” and national political figures with connections to the region.

Mr. Condron thinks a future branding effort could be based on biosceinces, Marcellus Shale or connected with the labor force, area educational institutions and the road and rail network.

In a diverse, large region, John Cognetti, a commercial real estate broker and chairman of Penn’s Northeast, sees multiple overlaying efforts that include biosciences, energy, tourism and perhaps other things.

“A lot of people have had a myopic vision of this region and what it could do,” he said. “Today’s economic development people don’t see those boundaries, and our vision has to change.”

With anticipated growth in shipping activity to the East Coast, Mr. Cognetti wants to play the region’s strong hand: as a logistics hub. Taking a page from Riverside County, Calif., and its “Inland Empire,” he’d like to pitch Northeast Pennsylvania as the “Eastern Inland Empire.”

“I’m going to use it,” he insisted.

Branding is art, science and psychology. A consumer product company may spend millions creating, reviewing and tweaking a brand and brand message and still get it wrong or have to do it over in a few years.

“We have yet to find that one easy description that both resonates outside the area and makes us distinct from other regions,” Mr. Condron said. “It’s not easy. But we continue to work on it.”

Contact the writer: dfalchek@timesshamrock.com