Scranton benefits from several key elements that help spur downtown renewal: preserved historic buildings; numerous government facilities and nearby hospitals, colleges and other institutions; and a daily influx of thousands of employees and others who work at or use those services.

While Scranton has a sprawling, 25-square-mile footprint, the downtown core — roughly seven streets by six streets — contains a critical mass of ingredients that fuel the main engine of commerce of the city and Lackawanna County, civic and business leaders say.

Over the years, the downtown had its ups and downs. Population decline led to a preservation movement sparked in the 1970s. In the 1980s, efforts began to construct a downtown mall as a savior. The Mall at Steamtown opened in 1993.

However, larger, changing retail and consumer forces and an economic recession took a toll on the mall and downtown, and both waned. At the same time, other larger forces, notably a trend toward more people wanting to live in a downtown, took hold in cities across the nation, and eventually made their way to Scranton. Private developers answered the call, by converting several older office/business buildings into residential apartments on upper floors, with retail spots at ground level.

Today, downtown seems on a decided upswing. The mall, now called Marketplace at Steamtown under a new owner, is undergoing a transformation. More people are choosing to live in apartments downtown, and cultural events regularly draw large crowds to streets, shops and restaurants.

Ken Okrepkie, chairman of Scranton Tomorrow, a community and economic development organization, said a growing number of folks living downtown adds to its vibrancy. An urban center where people merely work becomes deserted after the workday, but people also living there become part of the social and economic fabric. As the county’s largest municipality, Scranton’s burgeoning downtown also bodes well for the county overall, he said.

“What you have in the downtown is a community that’s really evolving and growing,” with private investors doing apartment conversions, Okrepkie said. “It adds to the revitalization of the urban economic center of Lackawanna County.”

■■■

The downtown’s story is one of evolution, first told in the many older buildings, now repurposed. To name a few: the former Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad station is the Radisson at Lackawanna Station hotel; the former Masonic Temple is the Scranton Cultural Center at the Masonic Temple; the former Scranton Central High School is part of Lackawanna College; the Catlin House is the home of the Lackawanna Historical Society; the former Immanuel Baptist Church is the University of Scranton’s Houlihan-McLean Center; the former First Church of Christ, Scientist is the Lackawanna County Children’s Library; the Brooks Building, formerly a brokerage office, hosts the Lackawanna County clerk of judicial records on the ground level and apartments upstairs.

The latter was one of the earlier examples of a growing trend of several former commercial buildings converted into apartments, noted John Cognetti, a Realtor and one of the founders in the 1970s of the Architectural Heritage Association, a preservation organization.

“It grew out of what was happening across the country,” Cognetti said. “It was a group of young people who came back to Scranton, artists and business types, interested in creating an awareness of Scranton architecture and seek redevelopment of it.”

■■■

Downtown Scranton retains many distinctive buildings stemming from the city’s inception 151 years ago as a cradle of the Industrial Revolution.

Built to last, many of these landmarks survive largely intact and are architectural gems of the downtown streetscape.

“We definitely have some good bones,” meaning old buildings, said Richard Leonori, an architect in Scranton who chairs the city’s Historical Architecture Review Board.

City Councilman Wayne Evans, a Realtor and longtime member of the Architectural Heritage Association, said the historic buildings downtown always wow visitors.

“Residents overlook it. You live here, you don’t look up,” Evans said. “When people come to town for the first time, they look up and go, ‘Wow, you’ve got some beautiful buildings here.’ ”

A guide to downtown architecture titled “History Set in Stone,” by the Lackawanna Historical Society and Lackawanna Heritage Valley Authority, details the early days and numerous notable buildings.

“By the late 1800s, Scranton had become one of the nation’s leading industrial centers,” the guide states. “Rich veins of anthracite coal, iron furnaces, thriving silk mills and several railroad companies drew blue-collar workers as well as ambitious entrepreneurs to the city. Prominent architects of their day and early residents shaped a cityscape that still exists.”

■■■

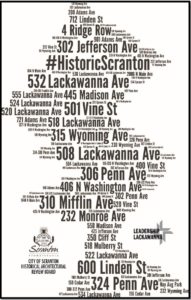

The grass-roots preservation movement and AHA grew in response to demolition threats to the city’s heart and soul, its significant and defining landmarks, according to a 2015 report by Leadership Lackawanna, a community leadership and professional development organization. As a class project, it updated HARB’s list of historic properties, to promote HARB and highlight the historic architecture of Scranton.

This group noted that an AHA emphasis emerged on education about Scranton’s unique architectural expression of its industrial boomtown history.

Redevelopment in the ’80s and ’90s in the form of the mall came with mixed emotions. A legal battle that ensued led to the 500 block of Lackawanna Avenue not being demolished or included in the mall, the Oppenheim and Samter’s store buildings were adapted into offices, and the city’s advisory HARB was created.

“All of it is an evolution over time, and we have highs and lows in Scranton,” Cognetti said.

The change is more fundamental than just Scranton, and is occurring nationwide, he said.

“What’s grown is the concept of downtown living,” Cognetti said. “So the trend is there and we’re seeing people wanting to be downtown.”

Evans noted that when he served on the city planning commission in the early 1990s, that board did a master plan that had a section on downtown calling for creating residential spaces on upper floors.

“We were talking about loft apartments back then,” Evans said. “Timing is everything. The issue of the downtown (renewal now) is that it was time. There’s almost a new urbanism taking root across the country.”

Apartment dwellers include young professionals and empty-nesters, Evans said.

“Downtown has grown organically, in a lot of ways,” Evans said.

More people living downtown adds to its critical mass and promotes more growth, said developer Charles Jefferson, whose holdings in the city include two downtown buildings he converted into apartments — the Connell and former Chamber of Commerce buildings, both on North Washington Avenue, as well as the Leonard Theater on Adams Avenue. His apartment buildings had 100 percent occupancies since each opened, he said.

Jefferson recently bought the former Samter’s department store/office building at Penn and Lackawanna avenues and plans to convert the upper floors into apartments and have retail spaces on the ground floor.

“Partly the success of downtown really is one building at a time,” Jefferson said.

■■■

A county seat, Scranton is home to the Lackawanna County Courthouse and government offices, as well as a federal courthouse and offices and city government.

Businesses, ranging from the large mall to small storefront boutiques, weave a retail fabric exhibiting both vibrancy and charm.

Various institutions including medical facilities, hospitals and colleges, either directly in, bordering on, or not far from downtown, drive thousands of workers and other people into and through the downtown daily.

The Commonwealth Medical College, a $120 million, four-story, 185,000-square-foot building along the 500 block of Pine Street, about four blocks from downtown, opened in 2011. Geisinger Health System took over the medical college late last year and changed its name to Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine.

About 32,000 people work in the city, many in the downtown.

One of the larger influences on downtown comes from the neighboring University of Scranton. Though mostly situated in the Hill and Lower Hill sections, the university has a few buildings downtown. In 2015, the university completed construction of the $47.5 million, eight-story Edward R. Leahy Jr. Hall at Linden Street and Jefferson Avenue.

The university’s presence, with 5,400 students, helped cement Jefferson’s decision to invest in Scranton, he said.

“It’s an awesome stabilizing factor,” Jefferson said of the university. “Anytime I get a chance to build next to a stable institution like that, I think it’s a pretty simple decision.”

■■■

The downtown and its aprons also boast special attractions, said Leonori and Cognetti. The federal Steamtown National Historic Site and adjacent county Electric City Trolley Museum and Station, off Lackawanna Avenue, nurture awareness and appreciation of the region’s train, rail and trolley history.

So, too, does the historic Iron Furnaces along Cedar Avenue, a short walk from Lackawanna Avenue.

Meanwhile, the Lackawanna River and its popular heritage trail form a western boundary of the downtown that provide a slice of nature in an urban setting.

“You have to tip your hat to the visionaries who decades ago saw the river as an asset,” and worked for its environmental restoration and creation of the trail mirroring the waterway, Okrepkie said.

What’s next?

Last month, Mayor Bill Courtright and a downtown advocacy organization called National Resource Network announced a new initiative to improve the downtown business district.

Under this plan, Scranton Tomorrow will lead the charge to increase Scranton’s capacity for economic development and revitalization.

Tools to accomplish that goal could include offering businesses and property owners tax incentives, renovating and repurposing old buildings to make them more attractive to buyers and planting trees and other greenery in downtown areas.

The nonproft Scranton Tomorrow, along with the city, the Greater Scranton Chamber of Commerce and Lackawanna County, developed in 2015, a revitalization plan for the America’s Best Communities contest in hopes of winning grants worth hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars.

Though that effort came up short in the competition, the plan served as a guide for when the city hired NRN, an initiative of the federal government’s Strong Cities, Strong Communities program, last year to assist with revitalization.

Now, the city and the other groups will take the next steps.

“I think we should be proud of where we are,” Okrepkie said. “We have a number of steps to take to move us forward.”

Contact the writer: jlockwood@timesshamrock.com, @jlockwoodTT on Twitter