NY Times –

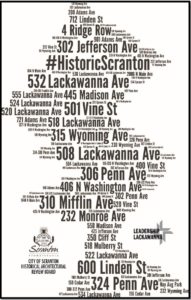

Scranton, Pa., may not be anybody’s idea of a boom town. A year ago, with the industrial city in northeastern Pennsylvania on the verge of bankruptcy, the mayor cut city workers’ pay to the minimum wage.

But Scranton still stands out as one of the American cities where poor people have among the best odds of climbing into the middle class, according to a large new study. A poor person from Scranton is almost twice as likely to rise into a higher income bracket than a poor person from Toledo, Ohio, or South Bend, Ind. By the measurements of the professors who did the research — four economists, at Harvard and the University of California, Berkeley — rates of upward mobility in Scranton are similar to those in Seattle, Boston and New York.

“I was one of those kids who quite honestly probably should have never went to college because I never had the money,” said Peter Danchack, who grew up in Scranton. His father repaired laundromat equipment, and before Mr. Danchack and his three sisters were born his mother worked in a dress factory.

At the University of Scranton, Mr. Danchack worked 35 hours a week while studying accounting full time and paid his way through college. One of his jobs was at a PNC bank branch. He’s now a regional president for PNC and lives in one of Scranton’s wealthier suburbs.

The authors of the new study found four factors that areas with more upward mobility tend to have in common: a large and geographically dispersed middle class; better than average schools; a high share of two-parent households; and populations engaged with religious and community organizations.

“Our neighborhood was very strong and supportive — everybody knew what everybody else was doing, but in a nice way,” said Ann L. Pipinski, a Scranton native who is now the president at Johnson College of Technology in Scranton. Dr. Pipinski and her sister were the first in their family to go to college, after having been raised by their mother and grandfather and mainly supported by welfare and their late father’s veteran’s benefits.

Another factor that sets upwardly mobile cities apart is that lower-class people live among the middle and upper classes: according to the study, there is a correlation between upward social mobility and income diversity.

James Mirabelli said that this economic integration was inspiring. He was born and raised in Factoryville, Pa., a borough of about 1,100 people 15 miles north of Scranton. His father was a truck driver and his mother worked at home. His family lived in a trailer park until Mr. Mirabelli was in fifth grade.

“You see what everyone else has and you say, ‘I want that, too,’” he said. “I got a little hungry by seeing what other people had or did.”

Mr. Mirabelli, who is 30, studied accounting at nearby Keystone College, and is now the financial administrator of the Abington Heights School District, which serves some of Scranton’s more affluent suburbs.

The study, based on millions of anonymous records, tracked people over the course of their lives to compare their family income as children with their family income as adults. About 26 percent of children who grew up in the 1980s and 1990s in Seattle families from the poorest fifth of the national income distribution have ended up in the top two-fifths today, for instance.

On the other end of the spectrum, the equivalent figure was 9 percent for Memphis natives, 13 percent for Atlanta natives and 15 percent for Indianapolis natives.

The figure was 27 percent for Scranton and 25 percent for Harrisburg, Pa., the state’s capital.

Harrisburg, like Scranton, has seen its share of financial difficulty, filing for bankruptcy in 2011. It also has an above-average rate of upward mobility.

Juanita Edrington-Grant, 59, spent most of the 1980s in and out of prison for dealing drugs. During her last stint in the state penitentiary, Ms. Edrington-Grant was able to take classes with professors from Pennsylvania State University, who taught courses toward earning certification as a paralegal. She left prison in 1992 and nine months later earned her associate’s degree from Penn State.

“It’s not easy trying to get help for ex-offenders,” she said. “It’s not easy working with them or getting help for them, because most people won’t give them a chance.”

She went to work for the Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry as a clerk and earned regular promotions. She retired this year from the Pennsylvania Department of State, where she worked as a paralegal, earning $50,000 a year.

Now, Ms. Edrington-Grant runs the Christian Recovery Aftercare Ministry, which provides services to ex-offenders and prisoners when they are about to be released and re-enter society.

Others who have overcome economic hardship also emphasize the assistance they received along the way.

Kristelle Coney, a 40-year-old single mother of three, worked at Washington Mutual for six years; she had never been to college. When her employer went bankrupt and was absorbed by JPMorgan Chase in 2009, she was laid off. She used her severance to pay for her first year of college at Lake Washington Institute of Technology in Kirkland, Wash., studying for a pair of associate’s degrees, one for premedicine and one to be a medical assistant.

“Once that year was up, I was able to use opportunity grants and Pell grants and student loans and focus on school,” she recalled, adding that food stamps also helped her juggle kids and school without working full time.

Ms. Coney, who graduated this year, works as a medical assistant at an obstetrics and gynecology practice in Bellevue, Wash., not far from her home in Redmond, where she pays higher rent to send her children to better schools.

Houston is one of the few Southern cities where upward social mobility is as high as cities in the Northeast and West, exceeding the rates of cities like Charlotte and Las Vegas. Roughly 22 percent of Houston children who grew up in the poorest fifth of the national income distribution have ended up in the top two-fifths today, according to the study.

In Houston, programs like Capital IDEA assist underemployed individuals who have obstacles in the way of furthering their education. In addition to helping pay tuition, Capital IDEA fast-tracks students through the remedial courses that can otherwise divert them from finishing their degree.

Adeline Garza, 25, was raised by her grandmother after her parents died. She dropped out of Texas A&M when she could no longer afford it. After struggling to find work, she took advantage of assistance from Capital IDEA, where she was encouraged by others in the same situation.

“We would always have weekly meetings to discuss our hardships, trouble with class, and help each other out. It’s a really great social support group,” she said. She’s about to start as a radiology technologist at St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital in Houston, with a starting salary of $45,000.

This post has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: July 22, 2013

An earlier version of this post misstated the length of time that Kristelle Coney, now a medical assistant, worked at Washington Mutual. She was there for six years, not 16.